Might as well face it, I am an art collector. Generally speaking, as an artist and art critic, I like to pretend that I don't even know any art collectors—that's what art dealers are for. But in truth, in my old age I have turned into an art collector myself.

I'm not the big-money kind of collector—you would probably have heard of me if I were—but I do own a substantial number of artworks. My apartment is filled with them, and I have more in storage. Until recently, many of these works sat on the floor, stacked in bunches against the wall—a situation any serious art collector will recognize.

I should also confess to harboring the occasional resentment towards art collectors as a group, solely by way of a minor family squabble, of course. As an artist, I find that far too many collectors have neglected to buy my work. And as a critic, well, critics everywhere resent collectors because they undermine their authority. As Sophocles might well have said about the art business, "Money talks, bullshit walks."

Still, the truth is that I do own a fairly large number of artworks, acquired over many years in all of the usual ways. I've gotten artworks through trade (a Mike Bildo Not Pollock splatter painting, for instance, in return for a portrait), as gifts (a David Wojnarowicz stencil of a snarling dog on a smashed metal garbage-can lid, a gift to my daughter—I'm her "regent"—on her second birthday), and via purchase (a painting on paper by the all-but-forgotten Abstract Expressionist Adja Yunkers, who taught a studio art class I took in college, which I bought for $500 at a Christie's Interiors auction).

Oh, and I once found a Martin Wong tondo in the trash on Ludlow Street, and then there was the day I was given a work by a friend after I said, "I want that!" I don't think the method worked any other time.

I've bought things because I liked the artist, and bought other things because I liked the dealer—or hoped the dealer would like me. I've bought lots of works for bargain prices at art benefits, notably a Louise Lawler black-and-white photo of a Maurizio Cattelan taxidermied mouse hanging like the hero of Ratatouille from a string tightrope, courtesy of the Printed Matter book fair.

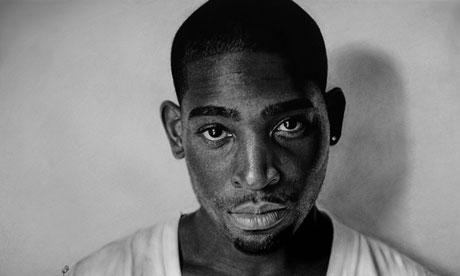

Once, in partnership with a dealer who was sitting next to me at a table at a benefit auction, I even managed to flip a work for a quick if modest profit after it turned out the two of us were the only people in the room who realized a gouache by then-little-known artist Kehinde Wiley was worth more than it was going for.

Every so often I catch myself, while looking at an artwork, imagining the reaction of visitors to my house when they see it on the wall. This simple sentiment, the pride of possession, is elemental to art collecting. Then I remember that I never have people over to my apartment.

Most amusing (to me) were my efforts to buy art "for investment." As I found out soon enough, the buying part is easy. It’s the selling that takes some doing. I can't tell you how many times I snapped up a work by a newly buzzworthy artist only to see the art market forget all about it six months later. Beware.

You might be surprised to learn that I was never much good at using my status as an art critic, such as it is, to build my collection. On occasion I've heard it suggested that the art criticism profession is corrupt, with good reviews being rewarded by the artist with gifts of art—some perhaps extorted rather than freely offered. Sadly, such has not been my experience. Perhaps the practice is more prevalent in Europe. Or maybe it's just me.

One of my favorite AA slogans is "come over to the winning side," and our time is undoubtedly the age of the collector. Money rules. You know it's true because the art critics are complaining about it so much. And odds are we'll never turn back the clock.

In the era of the 1 percent, the politics of art collecting—indeed, the entire art business—has been increasingly called into question. It's an old story. Balzac famously wrote in Cousin Pons about "a mania for collecting choice things" that masks "the vilest of deeds." Today's most sensational art headlines report inconceivably high auction prices that can't help but paint our top art buyers, whose identities are rarely exposed, as members of an oligarchy that seems completely alien to most of the human race.

Yet there's a lot more to the art world than the headlines. The artist Mark Kostabi notes that with 7 billion people in the world, if only half of them like beautiful things, we have reason to be optimistic. Indeed, go to any art fair—the Armory Show, which opens in New York in March, is a perfect opportunity—and look out over the scores of gallery booths, filled with bright and colorful things and the throngs of people who come to see and buy and sell them. This is the art economy, vital and full of joy, and it's powered by collectors of all stripes, with all their various desires.

Walter Robinson is an art critic who was a contributor to Art in America (1980-1996) and founding editor of Artnet Magazine (1996-2012). He is also a painter whose work has been exhibited at Metro Pictures, Haunch of Venison, and other galleries; Firecat Projects in Chicago presented a show of his new paintings in December 2012. This is the first edition of his new Artspace column, See Here.

http://www.artspace.com/