By Paul Mason Economics editor, Newsnight

Guerrilla illuminators bring Occupy protest art to the streets of New York

There has been so much art centred around the Occupy protests that it is beginning to feel like a new artistic movement. What defines it, and could it supplant the world of the galleries?

We get in the van and speed along to Bed-Stuy. It is the New York equivalent of London's Shoreditch or Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg, a hipster sub-metropolis, but with cuter beards.

I am with The Illuminators - a group of performance artists whose art is to shine revolutionary logos onto buildings in support of the Occupy Wall Street protest, including one that has become iconic - the 99% logo, known to protesters as "the bat signal".

In the van is not just a projector and a laptop, but also posters, a mobile library, and a whole vat of hot chocolate. The woman controlling the projector is a union organiser. The man vee-jaying the video is - well, a vee-jay (video jockey) in real life, but for corporates, fashion shows and the like.

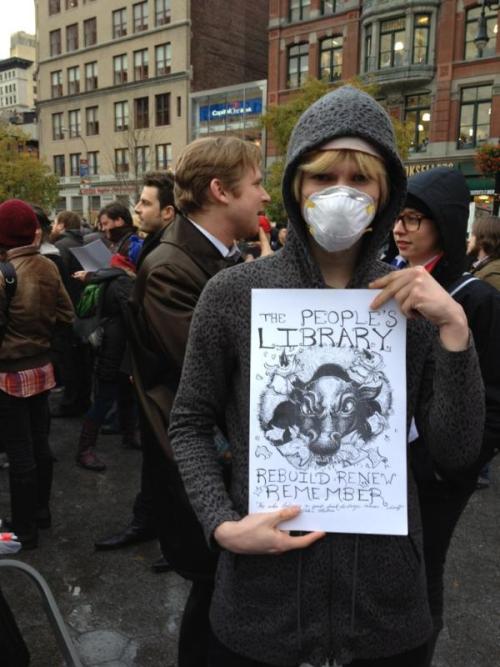

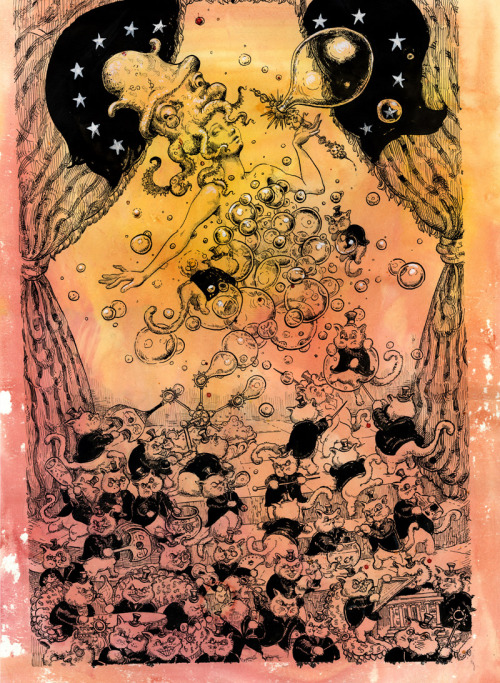

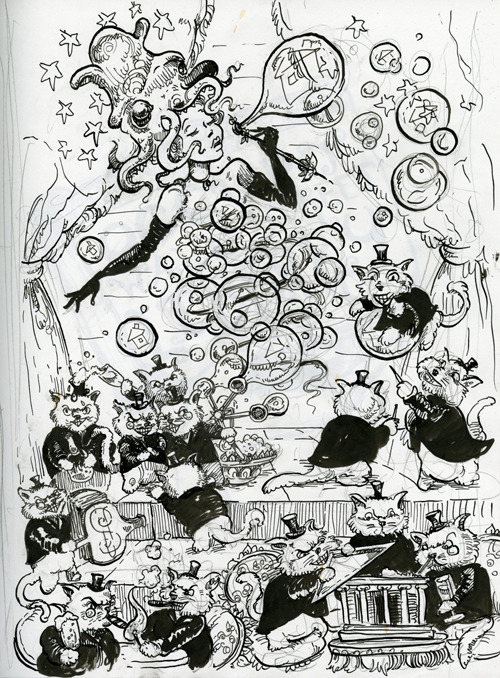

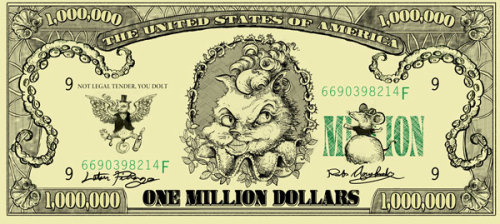

Molly Crabapple's Vampire Squid was appropriated by Occupy protesters across the US

Molly Crabapple's Vampire Squid was appropriated by Occupy protesters across the USAnd Mark Read, the driver and instigator, is a college lecturer in media studies.

"The bat signal is really simple. It's big and it reads as a bat signal - it's culturally legible," he says. It's a call to arms and a call for aid, but instead of a super-hero millionaire psychopath, like Bruce Wayne, it's ourselves - it's the 99% coming to save itself. We are our own superhero," he explains.

When Read and his collaborators shone the famous 99% logo onto the Verizon building, as protesters occupied Brooklyn Bridge in November 2011, one art critic called it "the most emblematic artwork" of the year, "the artistic gesture that stood for its rebel aspirations and its thwarted dreams".

Tonight they have a smaller scale work in hand. They get to Bedford, do a double sweep of the area as the cops move them on a few times, then unleash the full experience of Occupy projections, subversive Disney movies from the 1930s, hot chocolate, techno music and free books.

They get a good reception: Brooklyn is home to many of the "Gwaf" generation - "graduates without a future".

In the months since it was cleared from Zuccotti Park, the Occupy movement has been doing lots of culturally centred guerrilla actions around New York and other cities. So much so that it is fair to say that among youth, organised labour and some minority communities there is a bit of an Occupy zeitgeist going on.

Occupy Wall Street began in Zuccotti Park, in New York's financial district, in September 2011

Occupy Wall Street began in Zuccotti Park, in New York's financial district, in September 2011Which is why I am here. There has been so much art centred around the Occupy experience that it is, even this early, possible to ask whether we are seeing the emergence of an Occupy "style" - a tangible artistic movement in response to this major political event in American life that could upset the world of the white-walled galleries.

"It's been interesting," says Read. "A lot of the work coming out of Occupy is not concerned with how it will be perceived by a buying public. It's not designed to be bought, but shared - it's designed to be made available as widely as possible.

"It's attracted an audience, and wherever you get an audience you get art critics. The art itself is super 'copyleft' - people are putting out their work as posters."

Molly Crabapple is one of those who have contributed to the poster art. During the protest her acrylic paint and canvas strewn apartment, a few streets away from Zuccotti, became an impromptu salon for the graphic novelists, painters, illustrators and graphic designers who clustered around Occupy.

I think what Occupy did to my generation is it took us outside of ourselves. Outside of the gallery system, outside this very arid, self-referential way of working and it made us engage with real people, and the outside world”

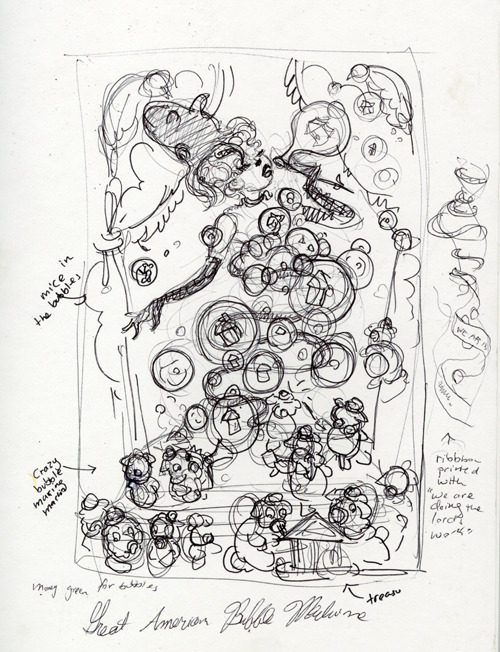

Molly Crabapple Artist Now she is hard at work on a major series of paintings on themes of protest and rebellion, entitled Shell Game. The most complete of the works shows a Vampire Squid, depicting Goldman Sachs, surrounded by a crowd of little fat-cat capitalists doing various unspeakable things in the style of a Bosch or Breugel painting.

"I started out just doing graphics - I drew this picture of an octopus with 'Fight the Vampire Squid' on its belly - and put it online and people used it as protest signs all over the country," Crabapple says.

"I think what Occupy did to my generation is it took us outside of ourselves. Outside of the gallery system, outside this very arid, self-referential way of working and it made us engage with real people, and the outside world.

"With my work for Occupy I am not just producing a cool, pretty image that decorates things, I am producing a functional and persuasive piece of work that's going to be pasted on buildings and held up by demonstrators."

When I try to do a piece to camera in the deserted, windswept concrete of Zuccotti not even my BBC press pass entitles me to stand in this quasi-public space.

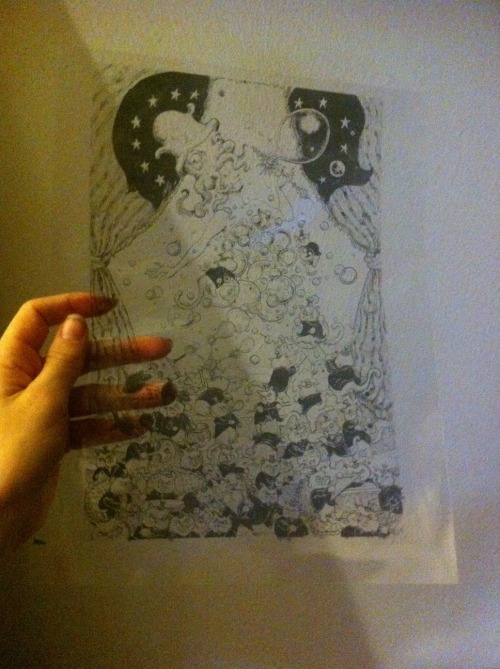

But the protesters have been sneakily busting back into the space under the cover of Zoe Beloff's performance project "Days of the Commune". This involves getting protesters and ordinary New Yorkers to rehearse, in full costume, a play by Brecht about the 1871 seizure of Paris by the working class.

Beloff, an experienced concept artist who will bring the work to galleries in Edinburgh (Talbot Rice Arts Centre) and Blackpool later this year, was mesmerised by the Occupy protest in Zuccotti Park:

"At first I just went down there and drew, documentary drawings. And I would observe and I began to think about the time when documentary drawing was socially relevant: as when Manet drew the dead revolutionaries after the Paris Commune.

This image of a dancer on a charging bull is one of the best known coming out of the Occupy movement

This image of a dancer on a charging bull is one of the best known coming out of the Occupy movement"I'd been, in my work, thinking about ideas of a utopian society abstractly and then suddenly it was - my god - it's just happening a few blocks from my house: I'd better get down there."

The work itself is more than just a play, for Beloff. It is about drawing out the parallels between the Commune "the first occupation of a city by its poor" and what the rebels at Zuccotti were trying to do.

It is not just in the visual arts that stuff is happening around Occupy. The protest movement has been a golden age for the various oppositional blogs and online magazines: n+1, founded in 2004, took up the various themes of Occupy early: student revolt; social injustice etc.

Another, The New Inquiry, grew out of an unofficial "salon" and illegal bookshop in a Manhattan apartment. Its founder, Rachel Rosenfelt, tells me she started it because she spotted a "surplus population" of talented young writers and artists left directionless after the economic crisis of 2009 ripped the heart out of the media business in New York.

"A year earlier we'd have been written off as hipsters, but nobody calls us that. What Occupy has done is created a spectacle of that youthful population: a spectacle of the simmering complaint that exists among that generation.

"It recognises there are in fact political stakes to our culture and our art - it's not about would-be academics and novelists daydreaming and writing for a small specialised group, it has made central to the cultural discussion the possibility of action."

Though TNI is not a magazine "about" Occupy, its writers and its subject matter clearly speak to an Occupy zeitgeist. But is it too early to identify an Occupy "movement" in art and wider culture?

It is certainly very clear what the artists involved are challenging: the world of the multi-millionaire concept artist, whose work is executed by what Crabapple calls "minions"; the white-walled gallery - with its air of non-committal, its preference for meaningless gesture, its reliance on interpretation by the viewer, and its extreme focus on commercialisation.

Zuccotti Park was cleared of the protest camp in November 2011, but the movement has continued

Zuccotti Park was cleared of the protest camp in November 2011, but the movement has continuedChristopher Kulendran Thomas, an artist and curator whose work spans London and New York, says:

"Occupy signals the limitations of what we've come to call Contemporary Art. Because the art of Occupy doesn't really work as Contemporary Art. It's bad art if you judge it in Contemporary Art terms because it's not open to interpretation.

"It uncritically uses the language of advertising to communicate: it goes where Contemporary Art can't go - because the latter is useless in situations of political urgency."

If there is an Occupy cultural zeitgeist what are its characteristics? Here's a speculative list:

- It is highly figurative (Crabapple points out that she and others come from the illustration craft, not fine art postgrad schools)

- There is an emphasis on typography

- Posters with artistic rather than strictly graphic design values are the norm

- The default "genre" is the graphic novel, with heavy influences of graffiti and graffiti art (Banksy, though a generation ahead of them, is one of the few mainstream artists they revere)

- And whereas for example "Pop Art" would subvert cultural icons as an act by the artist (think Warhol, Marilyn, Campbell's soup), here the subversion is done knowingly as a shared act between the artist and a mass audience that understands the concept of subverting icons as a normal cultural practice

And it is an art in search of ways beyond the multimillionaire-oriented art market to get to an audience.

The protesters have been returning to Zuccotti to perform Brecht's play Days of the Commune

The protesters have been returning to Zuccotti to perform Brecht's play Days of the CommuneCrabapple, whose work commands serious money now, recently used a web site called Kickstarter to "crowdsource" the funding for her paintings. She raised $64,000 from people who will not get the actual work, but who will get various souvenirs or sketches associated with it.

The money will support her while she does the work, but the actual paintings will sell at commercial prices:

"I thought that creating work that could only be bought by really rich people was silly. I started thinking of how I could break up the components so that people who were not that wealthy could participate in it."

These common themes - rejection of commercialism, a return to unironic figurative painting, a focus on mass, collaborative subversion of mainstream imagery and above all art with a social purpose - would be evidence of the beginnings of a new style under any circumstance.

But these themes coincide with a revolutionary new thought among art theorists - that the era of "contemporary art" as a whole may be over.

Kulendran Thomas tells me that if Lehman Brothers announced the death of neo-liberal economics, and the decline of the West, it would be logical for there now to be the death of an art that celebrated the freemarket age and the dominance of America:

I can't see what will emerge afterwards, anymore than I can see what the world economy might look like after Western dominance, but Occupy art can be seen as foreshadowing what replaces Contemporary Art”

Christopher Kulendran Thomas Artist and curator "Contemporary Art faces a potentially terminal crisis. Contemporary Art has sold itself as a non-specific, expanding, universal non-genre, much as neo-liberalism passed itself off as the natural state of things. The realisation that Contemporary Art is in fact a time-limited historical period, that can end, is a radical moment. But it's an idea that's gathering momentum."

"I can't see what will emerge afterwards, anymore than I can see what the world economy might look like after Western dominance, but Occupy art can be seen as foreshadowing what replaces Contemporary Art."

Next year will see the anniversary of a landmark in the birth of American modern art: The Armory Exhibition of 1913 introduced the United States to Cubism, Expressionism, Fauvism and the whole shebang of modernism in one, massive slamdunk.

By contrast, postmodern or "contemporary" art emerged - and modernism died - through a more protracted process.

If theorists like Kulendran Thomas are right then a significant event is happening: a new period of post-contemporary art may be opening up, with its early signals to be found in the graffiti, the graphic novels, light shows, street theatre, posters and figurative paintings associated with the Occupy movement.

Like modernism it has started with the sudden import to America of a meme of revolt from outside - though in this case from Tahrir, Syntagma and Trafalgar squares, rather than from the bohemian salons of Europe.

It is the art of outsiders: often craftspeople in the new workshops of the 21st Centuries - ad agencies, light-show technicians, graphic novel imprints, interior design groups. Its funding models - at least in this stage - are anti-commercial: much of it is in fact done "off the side of a desk" by people trying to hold down real-world jobs. And its aim, like Occupy, is to change American politics.

"There's a global uprising for democracy going on," says Read, "and these artists are trying to champion that movement".

Watch Paul Mason's Newsnight film on Occupy art in full

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-17872666

It's almost hard to believe that these beautiful images of eyes by Marc Quinn are extremely detailed oil paintings! Quinn's work "meditates on our attempts to understand or overcome the transience of human life through scientific knowledge and artistic expression." The title of the series, titled "We Share Our Chemistry with the Stars," appears to look more like space and galaxies than people's eyes, drawing on the idea of our eyes being windows to the world.

It's almost hard to believe that these beautiful images of eyes by Marc Quinn are extremely detailed oil paintings! Quinn's work "meditates on our attempts to understand or overcome the transience of human life through scientific knowledge and artistic expression." The title of the series, titled "We Share Our Chemistry with the Stars," appears to look more like space and galaxies than people's eyes, drawing on the idea of our eyes being windows to the world.

Gannet, 8" × 10", oil on panel

Gannet, 8" × 10", oil on panel Guillemont, 8" × 10", oil on panel

Guillemont, 8" × 10", oil on panel Puffin (Northern Lights), 8" × 10", oil on panel

Puffin (Northern Lights), 8" × 10", oil on panel King Eider, 8" × 10", oil on panel

King Eider, 8" × 10", oil on panel Swanlights, 14" × 11", oil on panel

Swanlights, 14" × 11", oil on panel Plover, 8" × 6", oil on panel

Plover, 8" × 6", oil on panel Northern Flicker, 8" × 6", oil on panel

Northern Flicker, 8" × 6", oil on panel Black Guillemont, 8" × 10", oil on panel

Black Guillemont, 8" × 10", oil on panel Beluga, 7" × 5½", oil on panel

Beluga, 7" × 5½", oil on panel