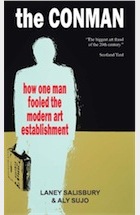

An illuminating view of the man who conned the art world grips David Pallister

Good art forgers have received what amounts to an endorsement

from an unexpected quarter. Promoting the National Gallery's forthcoming

exhibition Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries,

the director Nicholas Penny said: "I wish we had more fakes [in the

collection]. You only get good at spotting them by seeing them." Penny

touches a sensitive nerve in the secretive international art market

which, according to expert estimates, is awash with forgeries.

Astonishingly, some put the figure at up to 40%.

Forgers are a peculiar breed and money is only one motive. Anonymous by necessity, they yearn for recognition. Technically adept, often with formal training and a keen sense of colour and form, they have produced work, down to the singular brushstroke or cut of the clay, that rivals the originals. But, by definition, they have not found their own voice; they are unable to put their name to pieces of modest integrity and flair when they know that they are capable of simulating the greats. Lacking the prerequisite metropolitan social connections, they find the international art market – the galleries and auction houses of New York, London and Paris – intimidating, haughty and false: a mercenary, self-regarding conspiracy against the blooming of a thousand flowers. So beating the market is a challenge and a game: fraught with danger but ultimately exhilarating.

To varying degrees, of course, they are aware of the necessity for other technical subterfuges: the choice of paper and frame, the particular hue of the blue, the varnish and the sense of age – and how exactly did that painter scrawl his name? Experts who arbitrate authenticity often have only an instinct. "It's off," they might murmur. Or "It's not quite right."

It's extraordinary that John Myatt, an impoverished part-time art teacher and failed songwriter from Staffordshire, managed to get away with it for so long – producing more than 200 paintings over 10 years, which were sold around the world for a total of about £2m. With an aversion to the smell of expensive oils, which also took a long time to dry, he used house paint mixed with turpentine, linseed oil and lubricant jelly. His favourite targets were the modernists, the cubists Gleizes and Braque, Ben Nicholson, Nicolas de Stael, Giacometti and a dozen others.

But whatever doubts were harboured by the experts – and there were many – they were assuaged by that other essential ingredient of the good fake: the provenance. Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo, two American journalists, have produced a riveting and perceptive account of Myatt and his Svengali – the obsessive and enigmatic fantasist John Drewe, who, with charm and apparent wealth, insinuated himself into some of Britain's leading art institutions and then systematically falsified and corrupted their archives to create bogus histories for Myatt's fakes. The two men met in 1986 when Myatt, struggling to bring up his two children, placed a personal ad in Private Eye offering "genuine fakes". He was impressed when a Professor Drewe called and offered him commissions. It took a while before Myatt realised – only half-reluctantly – that he was being drawn into a gigantic fraud.

Drewe was in fact the son of a telephone engineer and had left school at 16. But, brimming with self-confidence and erudition, he passed himself off as a nuclear scientist as he cruised around London in his chauffeur-driven Bentley, dining the great and the good of the art world at expensive restaurants. The Tate was a particular target and his £20,000 donation earned him privileged assess.

Salisbury never met Drewe (he was sent to prison for six years in 1999). But she and Sujo (who died in 2008) have beautifully captured his manic, intense and unstable personality, one moment oozing with charm, the next with menace. The gullibility and the greed, deliciously described, make for compulsive reading. They have even caught his loose-limbed gait, his obsequiousness smirk, and strange staccato laugh disconnected from humour. I can testify to their uncanny accuracy. Shortly after his arrest in 1996 but before he was charged, Drewe pitched up at the Guardian with a convoluted and utterly improbable tale of being a high-level physicist involved in selling a secret cache of art to fund shady Balkan arms deals and much more. I was invited to his substantial house in Reigate to see his "evidence". At the time the Guardian was embroiled in its high-profile libel battle with the Tory politician Jonathan Aitken and, sure enough, the canny Drewe had inserted into one of his files an intriguing reference to Aitken.

Every one of his assertions that could be checked out proved to be a lie, and when confronted he flew into a rage, dashing off a five-page denunciation of me to the editor. It became clear later, when he drove the prosecution (and the judge) in the case against us to despair with his rambling, conspiratorial rants, that his approach to the paper was just another attempt to spread algae on muddy waters.

Drewe's downfall came from an unexpected source, which pitches Salisbury's tense narrative into the realm of thriller. In 1993 Drewe left his Israeli partner, Batsheva Goudsmid, an eye doctor, for another woman and wrongly accused her of mental instability and abuse of their children. Goudsmid took her suspicions and a briefcase full of Drewe's forgery kit, which he had left at their house, to the police. Scotland Yard's art and antiques squad were alerted and Goudsmid turned up two black rubbish bags full of incriminating documents. The story of the painstaking, two-year investigation that led to Drewe's appearance at Southwark crown court is a wonder.

And Salisbury is able to sign off with a happy ending. Myatt served four months of a one-year sentence and has since become a celebrity – selling "legitimate fakes", lecturing and starring in several TV series, the latest of which, Virgin Virtuosos, is currently being shown on Sky Arts.

David Pallister is co-author of The Liar: Fall of Jonathan Aitken (Fourth Estate).

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/apr/10/the-conman-salisbury-sujo-review

Forgers are a peculiar breed and money is only one motive. Anonymous by necessity, they yearn for recognition. Technically adept, often with formal training and a keen sense of colour and form, they have produced work, down to the singular brushstroke or cut of the clay, that rivals the originals. But, by definition, they have not found their own voice; they are unable to put their name to pieces of modest integrity and flair when they know that they are capable of simulating the greats. Lacking the prerequisite metropolitan social connections, they find the international art market – the galleries and auction houses of New York, London and Paris – intimidating, haughty and false: a mercenary, self-regarding conspiracy against the blooming of a thousand flowers. So beating the market is a challenge and a game: fraught with danger but ultimately exhilarating.

To varying degrees, of course, they are aware of the necessity for other technical subterfuges: the choice of paper and frame, the particular hue of the blue, the varnish and the sense of age – and how exactly did that painter scrawl his name? Experts who arbitrate authenticity often have only an instinct. "It's off," they might murmur. Or "It's not quite right."

It's extraordinary that John Myatt, an impoverished part-time art teacher and failed songwriter from Staffordshire, managed to get away with it for so long – producing more than 200 paintings over 10 years, which were sold around the world for a total of about £2m. With an aversion to the smell of expensive oils, which also took a long time to dry, he used house paint mixed with turpentine, linseed oil and lubricant jelly. His favourite targets were the modernists, the cubists Gleizes and Braque, Ben Nicholson, Nicolas de Stael, Giacometti and a dozen others.

But whatever doubts were harboured by the experts – and there were many – they were assuaged by that other essential ingredient of the good fake: the provenance. Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo, two American journalists, have produced a riveting and perceptive account of Myatt and his Svengali – the obsessive and enigmatic fantasist John Drewe, who, with charm and apparent wealth, insinuated himself into some of Britain's leading art institutions and then systematically falsified and corrupted their archives to create bogus histories for Myatt's fakes. The two men met in 1986 when Myatt, struggling to bring up his two children, placed a personal ad in Private Eye offering "genuine fakes". He was impressed when a Professor Drewe called and offered him commissions. It took a while before Myatt realised – only half-reluctantly – that he was being drawn into a gigantic fraud.

Drewe was in fact the son of a telephone engineer and had left school at 16. But, brimming with self-confidence and erudition, he passed himself off as a nuclear scientist as he cruised around London in his chauffeur-driven Bentley, dining the great and the good of the art world at expensive restaurants. The Tate was a particular target and his £20,000 donation earned him privileged assess.

Salisbury never met Drewe (he was sent to prison for six years in 1999). But she and Sujo (who died in 2008) have beautifully captured his manic, intense and unstable personality, one moment oozing with charm, the next with menace. The gullibility and the greed, deliciously described, make for compulsive reading. They have even caught his loose-limbed gait, his obsequiousness smirk, and strange staccato laugh disconnected from humour. I can testify to their uncanny accuracy. Shortly after his arrest in 1996 but before he was charged, Drewe pitched up at the Guardian with a convoluted and utterly improbable tale of being a high-level physicist involved in selling a secret cache of art to fund shady Balkan arms deals and much more. I was invited to his substantial house in Reigate to see his "evidence". At the time the Guardian was embroiled in its high-profile libel battle with the Tory politician Jonathan Aitken and, sure enough, the canny Drewe had inserted into one of his files an intriguing reference to Aitken.

Every one of his assertions that could be checked out proved to be a lie, and when confronted he flew into a rage, dashing off a five-page denunciation of me to the editor. It became clear later, when he drove the prosecution (and the judge) in the case against us to despair with his rambling, conspiratorial rants, that his approach to the paper was just another attempt to spread algae on muddy waters.

Drewe's downfall came from an unexpected source, which pitches Salisbury's tense narrative into the realm of thriller. In 1993 Drewe left his Israeli partner, Batsheva Goudsmid, an eye doctor, for another woman and wrongly accused her of mental instability and abuse of their children. Goudsmid took her suspicions and a briefcase full of Drewe's forgery kit, which he had left at their house, to the police. Scotland Yard's art and antiques squad were alerted and Goudsmid turned up two black rubbish bags full of incriminating documents. The story of the painstaking, two-year investigation that led to Drewe's appearance at Southwark crown court is a wonder.

And Salisbury is able to sign off with a happy ending. Myatt served four months of a one-year sentence and has since become a celebrity – selling "legitimate fakes", lecturing and starring in several TV series, the latest of which, Virgin Virtuosos, is currently being shown on Sky Arts.

David Pallister is co-author of The Liar: Fall of Jonathan Aitken (Fourth Estate).

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/apr/10/the-conman-salisbury-sujo-review

No comments:

Post a Comment