by Charles Thomson, co-founder of the Stuckists art group

In

1995, Damien Hirst defended his work with the rationale, "It's very easy

to say, 'I could have done that,' after someone's done it. But I did it.

You didn't. It didn't exist until I did it."

In 2000, he decided that doing it was not the justification after all:

"I don't think the hand of the artist is important on any level, because

you're trying to communicate an idea."

In 2006, the idea of the artist was not important on any level either:

"Lucky for me, when I went to art school we were a generation where we

didn't have any shame about stealing other people's ideas. You call it

a tribute".

In 2009, Anthony Haden-Guest interviewed Hirst: "Other artists have attacked

you for using their ideas. John LeKay said the skulls were his idea. John

Armleder … was doing spot paintings. And some say Walter Robinson did

the spin paintings first." Hirst's tribute was: "Fuck 'em all!"

Hirst's

career started In 1988 at the Freeze exhibition, when he painted

grids of spots with random colours. Thomas Downing, an American, painted

grids of spots with repeated colours in the 1960s. Gerhard Richter painted

grids of rectangles with random colours in 1966. John Armleder, a Swiss

artist, painted spots during the 1970s.

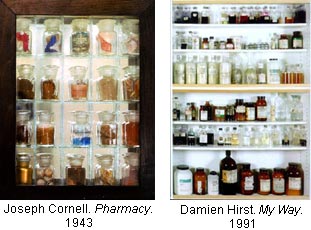

In

1989, Hirst starting making cabinets with bottles on shelves. In 1992,

he developed this into a room-size installation, called Pharmacy.

Joseph Cornell displayed a cabinet with bottles on shelves, called Pharmacy

in 1943.

In

1991, Hirst exhibited a preserved shark in a tank in Charles Saatchi's

art gallery in St John's Wood. Eddie Saunders exhibited a preserved shark

on a wall in his J.D. Electrical shop in the YBA heartland of Shoreditch

in 1989.

In 1992, Hirst moved to New York, where he met John LeKay, a 31 year old

British artist, resident in the city since 1981. Hirst was four years

younger, a celebrity in the UK, but still only four years out of college

and exhibiting in his first show (of twelve British artists) in the United

States. LeKay said Hirst "told me one time he was going to conquer America

like the Beatles."

LeKay

kept a journal. He recalls that Hirst visited his studio on several occasions

and showed considerable interest in his work. Hirst was working on "patch

paintings", which he abandoned after LeKay told him they were "shit" -

"The concept was brush marks on Francis Bacon's studio wall. Looked like

his grand mother made them."

They met frequently over the next few months, visiting each other's homes

and going to art openings, shows, parties and bars, sharing meals, getting

drunk together and playing badminton with a beach ball in the living room.

LeKay said Hirst was "a raging alcoholic and cocaine addict. He was always

snorting it. Drinking like a fish … He seemed to be really lost at times.

If he was not drinking or doing drugs, he seemed to be depressed. I gave

him some advice about this one time."

Contributing to Hirst's state of mind was the Turner Prize result in November

1992. LeKay said Hirst was "Angry about it. He seemed shocked he did not

win it."

LeKay, raised a Catholic like Hirst and described by Adrian Dannatt in

Flash Art as a "strung-out enfant terrible", was a kindred spirit,

if not a role model. LeKay recalled: "One time in the taxi going to Ashly

Bickerton's house, he said that he thought he was becoming me. Talking

and acting like me. It was very strange … I thought he was mentally ill

at that point or on coke."

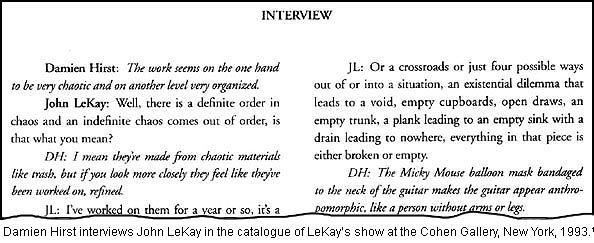

Hirst

was sufficiently engaged to edit the sixth - and, as it turned out, final

- issue of LeKay's Pig (Politically incorrect geniuses) magazine,

enlisting Danny Moynihan, Marcus Harvey and Angus Fairhurst as contributors.

He also interviewed LeKay for the catalogue of LeKay's show in 1993 at

the Cohen Gallery, managed by Tanya Bonakdar, who had given Hirst his

first US solo show.

Hirst

mentioned that he was looking for a source of butterflies, and LeKay gave

him a spare copy of the Carolina Biological Supply Company Science

catalogue, which he had been using as a source of ideas. They reached

an agreement, said LeKay: "I put yellow stickers on the pages with the

skeletons, skulls, mannequins and resuscitation dolls I was working on.

He said he would stick to the animals and I would do the humans and he

was very happy."

Another time, LeKay showed Hirst a photo of one of his works, a split-open

sheep in a crucified posture. Hirst asked its date and - when told 1986

or 87 - became very quiet. "He got fidgety, bugged in the ride back in

the car to the city. Began making odd comments out of context. At the

time it made no sense. Then the next morning Tanya called me frantic,

telling me he smashed up the kitchen he was staying at. She said, ''what

the fuck did you say to him?' "

"I

said, 'Nothing. All I did was show him slides of my old work, the meat

pieces, to let him know I had done work like he was doing years before

him. To me it wasn't a big deal, but to him it was for some reason. If

I knew it would have upset him so much, I would never have shown the slides

to him.' She said, 'You have no idea how envious he is of you.' "

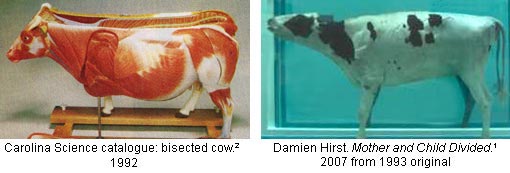

LeKay's gift of the Carolina Science catalogue manifested as a

dramatic development in Hirst's oeuvre within a few months. One of the

items illustrated was a model cow bisected lengthways. In the 1993 Venice

Bienniale, Hirst exhibited Mother and Child Divided, a cow

and a calf bisected lengthways.

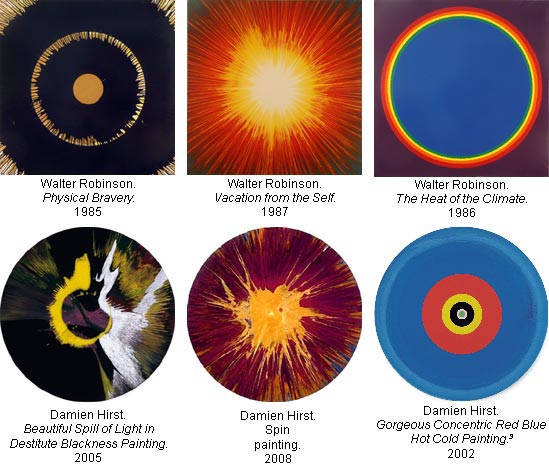

In

1995, Hirst started making "spin paintings", the titles of the first four

all beginning with the word "beautiful". Spin paintings - made by pouring

paint on a revolving surface - appeared in the 1950s as a popular novelty

activity and had also been made by artists. Swiss artist, Alfons Schilling,

and French artist, Annick Gendron made them in the 1960s. Walter Robinson,

an American artist, exhibited them during the 1980s. John LeKay developed

his own variant called "pour paintings" - which Hirst saw early in 1993

- by using a table which could tilt and swivel. LeKay says Hirst told

him they were "beautiful and sexy".

UK artist, Andy Shaw made spin paintings in 1993 and said that he talked

about them to Jay Jopling, who represented him and Hirst, a few months

before Hirst began to make his them. Hirst showed some in his 1996 show,

No Sense of Absolute Corruption, at the Gagosian Gallery in New

York. David Rimanelli in ArtForum said the only difference between

Robinson's and Hirst's was that some of Hirst's had motors to make them

rotate. LeKay said Hirst had paid particular attention to one of his "pour

paintings" that was "hanging on a toilet paper holder of a wall pierced

through its centre to make it rotate."

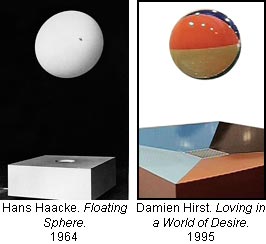

One

of Hirst's exhibits in the 1996 Gagosian show was an installation of a

ball held aloft in a jet of air. Hans Haacke made an installation of a

ball held aloft by a jet of air in 1964. Haacke used a white ball. Hirst

used a coloured ball.

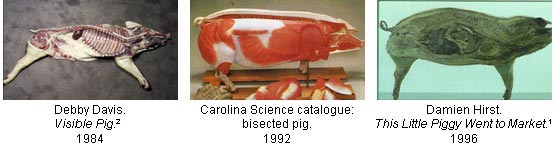

Another Hirst exhibit was This Little Piggy Went to Market, a pig

split in two lengthways (in vitrines of formaldehyde). One of the pictures

in the Carolina Science catalogue given to Hirst by LeKay was an

anatomical model of a pig split in two lengthways. In 1984, Debby Davis

took a cast of half a pig cut open lengthways and made a fibreglass sculpture,

called Visible Pig. It was sold by Doug Milford of the Piezo Electric

gallery in January 1986 to Charles Saatchi, and auctioned at Christies,

New York, in November 1989.

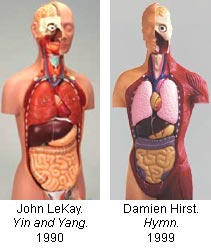

In

1999, Hirst made Hymn, an enlarged version of an anatomical torso

model from Humbrol. One of LeKay's found object works from 1990 was Yin

and Yang, an anatomical torso model from Carolina Science.

In 1999, celebrity chef, Marco Pierre White made a picture, Rising

Sun, to decorate his restaurant. He said that Hirst copied it a few

months later with a work called Butterflies on Mars and, according

to White, told him, "I'm the artist and you're the chef so everyone's

going to think you've copied me."

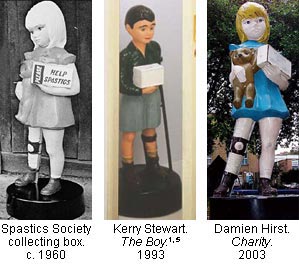

In

2003, Hirst made Charity, based on the model of a girl with a collecting

box displayed from the 1950s to the 1980s by The Spastics Society (now

renamed Scope). In 1993, Kerry Stewart, made The Boy from the Chemist

Is Here to See You, based on the Society's model of a boy with a collecting

box. Her work was part of Saatchi's Young British Artists shows

in the 1990s.

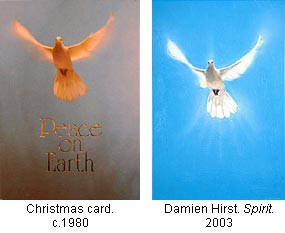

In

2003, Hirst painted Spirit, a dove in the sky with wings aloft. The same

image had been painted multiple times and exhibited for the previous four

years by Talaat Elshaabiny on the Bayswater Road. It was originally from

a 1980s Christmas card.

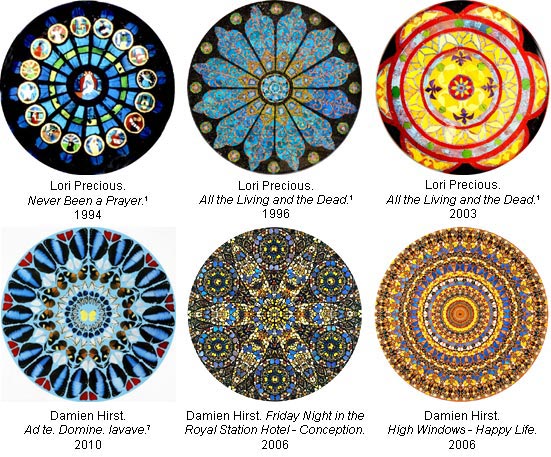

Hirst

exhibited artworks with butterflies in 1991, using whole butterflies scattered

on a painted surface. Lori Precious, a Los Angeles artist, started using

butterflies in 1992. She fixed the wings contiguously to create the effect

of stained glass windows. In 2003, Hirst started fixing butterfly wings

contiguously to create the effect of stained glass windows. Precious's

work in 2005 was titled with a literary quote from James Joyce. The titles

of Hirst's butterfly stained glass works in 2007 incorporated literary

quotes from Philip Larkin.

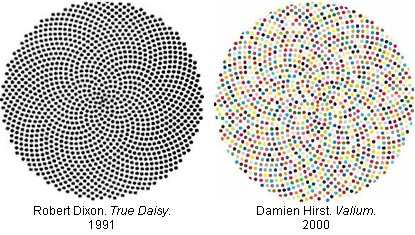

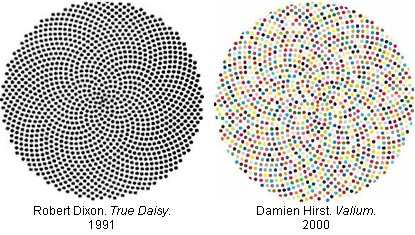

In

1991, True Daisy, a complex design of spiralling spots within a

circle by Robert Dixon, a mathematician and computer artist, was published

in The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry.

In 2003, Hirst contributed a design to The Guardian's colouring book for

children. Dixon said Hirst's design was "exactly the same" as his one.

Hirst's manager replied it was not copied from Dixon: Hirst had found

it in a book called The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting

Geometry.

In 2006, Dixon discovered that Hirst had also used True Daisy,

with the spots coloured in, for Valium, an edition of 500 prints

produced in 2000.

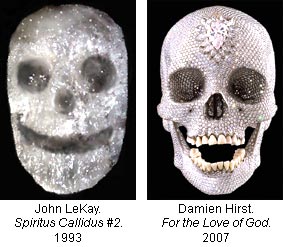

LeKay's

1986 work of a split-open crucified sheep, which had caused Hirst so much

upset, was titled This Is My Body, This Is My Blood. In 2005, Hirst

did a split-open crucified sheep, titled In the Name of the Father.

LeKay's was on a board. Hirst's was in a tank of formaldehyde.

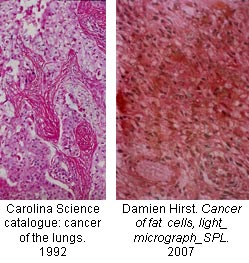

In

1993, LeKay made paintings based on images of cancer cells from the Carolina

Science catalogue. Hirst saw them. In 2007, in Beyond Belief

at the White Cube gallery in London, Hirst exhibited paintings based on

images of cancer cells from the Science Photo Library.

In

1993, LeKay produced a series of 25 skulls, some made out of paradichlorobenzene

and one made from soap covered with Swarovski crystals. Samples had been

in the Cohen Gallery. LeKay says he mentioned the idea of a skull covered

in diamonds to Bonakdar. In 2007, Hirst made a skull covered in diamonds.

LeKay used a title, Spiritus Callidus, a name for the devil. Hirst

called his For the Love of God.

In

2009, a year after he had divested himself of his stock of conceptual

and minimal art at the famous Sotheby's auction, Hirst announced that

conceptual and minimal art were "total dead ends" and that he "always

thought painting was the best thing to do".

http://www.stuckism.com/Hirst/StoleArt.html